This is the story of a voyage of the 3-masted schooner "Neptune 2" in 1929. Setting out from St. John's, N.F. the intended trip to Bonavista Bay should have taken about 12 hours, but 48 days later, she arrived off the west coast of Scotland, having been literally blown across the Atlantic. This account of the remarkable voyage and the privations endured by the crew is toldby JOHN BEAUMONT

ATLANTIC

EPISODE

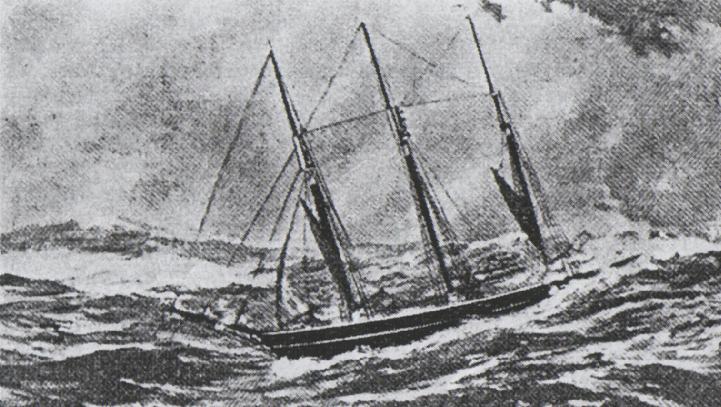

Reproduction of a painting by Anton Otto Fischer,

of the "Neptune 2" running before the wind in mid-Atlantic

ON November 29, 1929, the 126-ton 3-masted schooner Neptune 2 left St. John's, Newfoundland, on what was normally a trip of 12 hours, bound for Bonavista Bay. On board this Danish-built vessel, constructed of oak, were her captain, Job K. Barbour, and the mate, Bertie Barbour; the cook; and three seamen. There were also five passengers, one of whom was a woman, Mrs. Humphries.

Normally the nine-year-old schooner, owned by Capt. Barbour and his uncle, carried seal and other skins as cargo. On this voyage, because Christmas was approaching she carried a few cases of oranges in addition to more general goods. Mrs. Humphries had bought a bottle or two of wine and this, together with the fruit, were to help save the lives of everybody on board.

Forty-eight days later, after hope for her had been abandoned, the Neptune 2 dropped anchor in a perilous tideway off Ardnamurchan Point, Scotland, having been literally blown across the Atlantic, for she had no other means of propulsion except her sails.

"The Oban Times" dated January 25, 1930 described the voyage "across the Atlantic from the Newfoundland coast to the shores of Argyll," as "one that perhaps has few parallels in the annals of the sea."

It was fortunate, indeed, that all the male passengers were themselves experienced sailor men. The boatswain, Peter Humphries, the oldest on board and husband of the woman passenger, said afterwards:

"When almost within sight of our homes at Bonavista Bay we encountered a terrific gale and heavy snow which forced us to run under bare poles for 220 miles. The seas were terrific and in all my 40 years' experience as a New foundland fisherman, I never encountered worse. While I was taking my watch at the wheel one sea engulfed the entire poop, swept away our wheelhouse, smashed both life-boats and damaged our steering-gear. I was thrown against a little deckhouse and rendered unconscious, but fortunately I got mixed up with some ropes, and this kept me from being swept overboard.

"The wind changed, and by fixing up temporary steering-gear we endeavored to sail back to St. John's. We made good progress for two days but then encountered more head winds which increased to gale force, and once more we had to run for it. For four days we kept the vessel before the wind and then found ourselves about 300 miles south-east of St. John's and we hove-to for four more days. We spoke to a large passenger liner on December 14 and sent a message aboard her. . .

Capt. Job Barbour does not, to this day, know why he did not ask this liner, one of the White Star fleet, for fresh water and provisions before she sailed away. Four days later, another steamer bore down on the schooner during a brief period of daylight, but, being coastal seafarers, none of the Neptune 2's complement could understand the signals she made by flag-hoists and she, too, disappeared. But to continue Peter Humphries' account:

"After we had drifted some days, the weather worsened and, on December 21, we decided that our only hope of saving our lives was to try to make across to Britain. We had only a compass and without other instruments it was impossible to take any bearings. Our captain shaped a course which he thought would bring us to the English Channel."

Severe though the ordeal was proving to all on board the schooner, not least to the woman, the poverty of the situation had by no means been plumbed.

At first only mildly seasick, Mrs. Humphries became quite seriously ill and had long been confined to her bunk in the deckhouse, until one day a great sea ripped off its roof and left the sick woman protected only by the four bulkheads. Then they carried her, almost unconscious, to the foc'sle in which there already was an injured crew-member, and where all were to live for many days to come.

Water became contaminated by salt so that even a cup of tea, when they could boil water in the galley, was barely drinkable. Provisions, although carried in a quantity which would have sufficed for several coastal voyages between Bonavista and St. John's, were running at a dangerously low level. It was then that those cases of oranges proved providential, and the fruit were rationed out at the rate of three per day per person. Mrs. Humphries could not eat. Instead she was sustained on spoonfuls of her Christmas wine.

To a reporter she described her plight and that of her companions: "We expected to spend our Christmas at home along with other members of our

A recent photograph of Capt. Job Barbour

Foto-Newfoundland

family. Instead, Christmas Day saw all hope of making home abandoned, as we were heading straight for whatever land we might make on the other side of the Atlantic.

"I was confined to the forecastle along with the rest of the crew, as it was impossible to remain aft owing to the tremendous seas which were continually being shipped. What with the confined air of the small space of the forecastle and the anxiety, I was completely prostrate."

This was perhaps understatement. For many days the wheel was lashed, and the captain, crew and passengers remained below, for to go on deck during the days when the storms were at their height would have been foolhardy and, perhaps, attended with disaster.

Considering the battering the Neptune 2 was receiving and was still to take, the schooner sustained remarkably little damage except to her super structure, to the wheelhouse and bulwarks and to one of her spars which was brought down by the wind, went over the side, and had to be cut free lest its pounding damaged the ship's side. The pumps were never required during the whole period of her drifting.

Coal for heating was now becoming very short although extra supplies were in one of the compartments in the cargo-space and could not be obtained because of the weather. Christmas came and went. The celebrations consisted of their managing to boil a kettle of their meager supplies of sweet water, and the main festive meal was of some onions and bologna-sausage broached from the cargo. This was their second full repast in almost one month.

All deeply religious, the ship's company prayed regularly, ending always with: "Better tomorrow, please God." Afterwards, they freely confessed that their faith as to ultimate survival was sternly tested though never broken. Mrs. Humphries, expected by some of them to die, appeared instead to rally as the New Year came in.

As the weather sometimes moderated, Capt. Barbour kept all except the invalids busy on a multitude of small tasks, one of them being the repair of the severe damage to their canvas over which, when frozen previously, Job Barbour recalls pouring precious paraffin in an attempt to render them free of ice. He was then in his late twenties, and has outlasted his schooner which, having been sold a few years afterwards, foundered on her first voyage for her new owners who had despatched her, deeply laden, with a cargo of fish.

After confessing: "I was quite ignorant as to our position, for our usual route was seldom out of sight of land," he described the last few days of the epic voyage.

"When nearing the coast," (exactly which coast he was extremely doubtful) "the weather, for January, became much warmer, and we supposed we were coming to Africa . . ." This calculation of Capt. Barbour's was hundreds of miles in error.

The days dragged on. On January 9, one man thought he saw land. This proved but a dark cloud but everybody aboard now began to realise with uncomfortable certainty that, if they were not sighted soon by another vessel or if they did not make a landfall, they would perish from thirst and the effects of their long ordeal. The remainder of the oranges had long since gone rotten.

On January 13, it was fine and clear, and, with some sail set and the wind abaft the beam, the little schooner was sailing comfortably, albeit slowly. Sea- birds began to fly around them.

Night fell, and then the lookout's shout: "A light!" acted on all like a tonic. The light, surely, was from one of the Scillies? Capt. Job was uneasy. If this was the English Channel, should they not be surrounded by other ships?

From a chart which they had found on board after they had been at sea for a month they had learned the lights which they expected to see by heart: the first would be the Scillies~ne flash every 20 seconds; then Wolf Rock, Plymouth or Eddystone, a double flash every half-minute. Yes, they would know exactly how to shape their course when they saw these ocean signposts. But this light, the first indication of human habitation for weeks, this was none of these.

Daylight revealed no land, nor were there any ships. It came on to blow again and the ship barely had steerage-way. With a blessed return of fine weather, Job decided to take a sounding. The lead ran out to many fathoms before it slackened.

"Bottom!" Job yelled excitedly. There were shouts and cheers and the good news was relayed to Mrs. Humphries who declared, weakly, "We'll be in harbour before the day's out."

But Capt. Barbour was cautious. "We can't have any guarantee of that. If we're lucky and see land, it doesn't follow that we'll be spotted by another vessel which can pilot us in. And perhaps there'll be no people ashore to see us, anyway."

The ship's company will always remember the elation they felt when land was at last espied. All filthy dirty, sore from their buffetings, hungry, tired and above all thirsty, they momentarily forgot all these as in the half-light of what was going to be a fine day they could see islands close to them, the hills covered by snow, and the beam of a lighthouse. They counted, and waited. Yes, that was the Scilly light. But was it? And there were others which were faint but still identifiable by their frequencies. No, something was wrong some where. These were not the Scillies, Wolf Rock or Eddystone. Where were they sailing? The latest light was up on a high cliff. When the Neptune 2 was about a mile or so from the land, they hove-to until full daylight.

Later, they picked their way among the many islands which now appeared both to port and starboard and ahead. One of the crew saw another object. "Steamer coming!" he roared to Job Barbour. "We must be in the English Channel after all!" There was not one ship, but at least half a dozen. But the nearest indicated that she had no interest in the battered schooner with her rags of sails. There was an old muzzle-loading musket on board, made a century before, but still capable of being fired. With the powder, this sounded like a cannon to the schooner's complement. As a crew-member bent a flag to the halyards and jerked it up and down, the steamer sailed toward them. They were to be saved! Job shouted. "Which land are we off?"

From the other ship's bridge came an answering hail but nobody understood what was said. Nearly frantic, Job called: "We want water!" and made a pantomime of drinking. Again they were not understood.

"Our boats are smashed. We don't know where the harbour is..." But the steamer's crew just gazed; she started to draw away despite the despairing shouts from all in the Neptune 2. It was incredible that nobody on board the steamer wanted to more thoroughly investigate their plight. They tried to read her name but this was indecipherable. She disappeared.

Stifling the cruel disappointment he felt, Capt. Barbour headed his vessel for two large islands some miles ahead, and all that same day, the schooner crawled toward them. At least, they appeared to offer safe anchorage. The lead was kept going constantly; Job did not intend to ground his vessel now; and, just in case it should be required, the mate and a passenger worked desperately to try to repair one of the smashed dories.

Late that afternoon, houses and people were easily seen on one island, and so were three slender masts of a wireless-station. Barbour was confident that, ere night fell, their relatives in Newfoundland would learn of their safety. There was a wharf, and small sailing craft edging up the coast.

Out came their old gun again and they fired it joyfully. The boat turned, and its crew of three guided her toward the Neptune 2. Then fate intervened once more. A sudden squall blotted out the sight of everything, and under spanker and mainsail the wind and tide swept the small ship some i~ miles away from what they considered would have provided a haven and journey's end.

That night was brilliantly moonlit until before-dawn clouds plunged them into darkness. As the day came, so did the wind and it took the efforts of two at the wheel to steer through the tide-rips. But they were never far from their "Number One" island which had seemed to offer them salvation, and when near a sandy cove they made the big decision. They anchored, for the first time in 48 days. But where were they?

They saw one of the lighthouse keepers waving, but others on shore ignored them. The receding tide uncovered a huge rock which they had scarcely missed on the way in. Its presence also warned that, if the wind veered, they would be wrecked, so, amid all the semaphoring from ashore, they persevered with the repairs to the dory, meanwhile banging away with the old musket.

By evening, it was impossible for them to move from their anchorage with out running ashore, for the tide was running at a rate of knots. Their danger was as great as it had ever been. Night was almost upon them when the

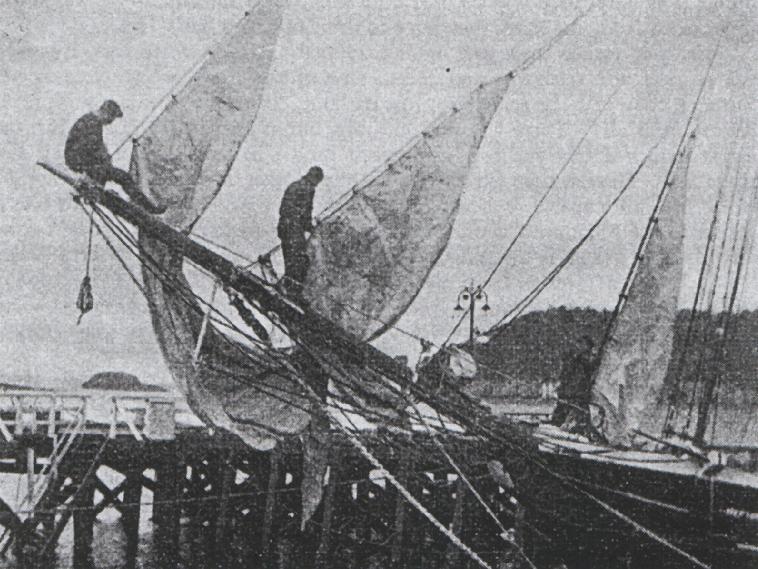

This picture of three crew-members on board the "Neptune 2" was taken during her refit in Scotland

wheel which, today, still hangs in the Newfoundland offices of E. and S. Barbour, marine agents, Water Street, St. John's.

The firm sells the brand of engine which, supplied by Mr. Bergius (who read of the voyage) to get the Neptune 2 back across the Atlantic, was to commence a long trading partnership with the famous Kelvin company.

Last year, Capt. Barbour was asked what he thought of his new 1930 Kelvin engine on the way back home. His reply was short: "It never stopped until we turned it off at St. John's," he said.

The writer wishes to acknowledge the assistance he received in compiling the story which came from several sources. First, Capt. Barbour himself, who also supplied a photograph of himself today, and a bow-view of the schooner. The "Oban Times", from whose account we used quotations noted by that paper at the time. The "Daily News"; published in St. John's, which in 1965, re-serialised the story of the voyage. Bergius Kelvin of Glasgow, whose sales manager gave valuable items of information. The "St John's Woman", whose proprietors ran the story over four issues in 1964. And lastly, Mr. J. H. Moyes, of Steers, Ltd., St. John's, Newfoundland whose representative first told the writer of the voyage on a recent visit to' the U.K. and who subsequently acted as the most patient and willing messenger for him and Capt. Job Barbour.

Time has passed. One would havc thought that the film-moguls would have long ago pounced on the story and given it back to the world in colour. But they would have needed a love-interest, added to and possibly spoiling - the true story of the Neptune 2's 48-days adrift.